Phase 5: Community Supervision

The majority of impaired drivers do not receive lengthy terms of incarceration. Instead, most will serve their sentence in the community under the supervision of probation officers. With criminal justice and prison reform initiatives gaining support, greater emphasis is now placed on reducing rates of incarceration and allowing non-violent offenders to remain in the community.

Of the more than 4.5 million individuals subject to community supervision orders, at least 15% have one impaired driving conviction on their record, and approximately 8% are repeat DUI offenders.

Community supervision aims both to protect public safety and to encourage behavior change. To be effective, community supervision officials should rely on the use of validated assessments, proven methods and interagency partnerships.

DUI offenders are a challenging population to supervise, and they tend to be inconsistently supervised due to varying procedures across jurisdictions.

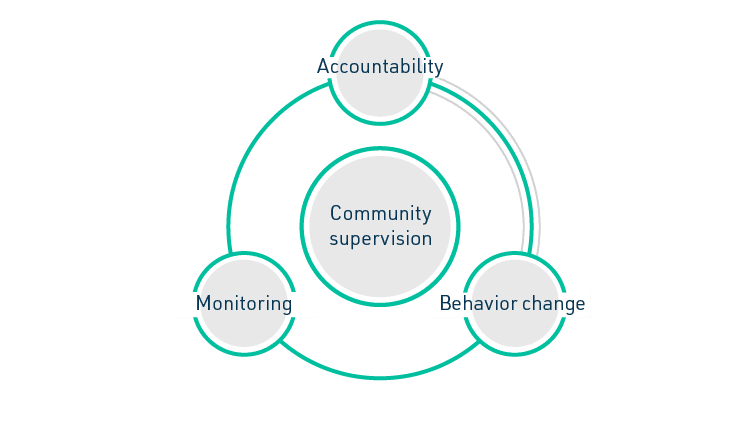

To deal effectively with high-risk impaired drivers, the focus must be on requiring an appropriate level of services and simultaneously addressing the underlying criminogenic needs that lead to offenses. Changing behavior and ending or preventing recidivism requires identifying and treating substance use disorders, mental health disorders, and trauma. Too often, the system operates like a revolving door. But when monitoring, accountability, and treatment occur together, community supervision agencies can facilitate long-term behavior change.

What is community corrections?

Not every impaired driver is sentenced to a period of incarceration. Many offenders, particularly first offenders, may not serve any time in jail. Even when incarcerated, most impaired drivers serve only short terms unless they have a long criminal history or are convicted of causing serious bodily injury or death. Community corrections is the overarching term that describes the supervision of justice-involved individuals who are not incarcerated.

The United States has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world and spends a staggering amount—more than $81 billion—on corrections annually, and in recent years, there has been a shift away from mass incarceration. With the signing of the Second Chance Act in April 2019, more funding and grant opportunities are now available to community supervision agencies.

The authority or agency that oversees community supervision varies from one state to another although there are several common administrative models:

- State supervision – most community supervision agencies who deal with felony offenders operate at the state level.

- County/local supervision – other supervision agencies are funded and operate at the county or local level, which creates variance within a state.

- Combined supervision – some states take a combined approach whereby the state assumes responsibility for funding community supervision, but programs are administered at the county or local level.

- Federal supervision – individuals charged and/or convicted of federal crimes are subject to community supervision that is administered by the federal court system.

Community supervision offers two advantages. First, it is far more cost-effective to supervise someone in the community. Data compiled by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts reveals that detaining an individual pre-trial and then incarcerating that offender post-conviction is approximately eight times more costly than supervising someone in the community. The former costs in excess of $30,000 per year whereas the annual costs associated with community supervision are slightly over $4,300.

Second, community supervision often offers greater potential for rehabilitation and recovery as an offender can remain active within the community, maintaining employment, preserving family ties, establishing social networks and more.

At the end of 2016, an estimated 4,537,100 adults, or one in every 55, were under community supervision. The two most common types of community supervision are probation and parole.

Probation

Probation is the most common form and refers to a period of monitoring that the court imposes on an offender. Roughly 514,000 offenders on probation are impaired drivers.

Probation is frequently ordered in lieu of imprisonment. In instances where a short period of incarceration is statutorily required, the offender will serve the sentence and then be subject to probation.

An individual is generally either subject to active probation or banked/administrative/paper probation.

An offender with an active probation status is required to report to or have contact with his/her probation officer on a regular basis to monitor compliance and progress. Most repeat or high-risk offenders will be actively supervised. Some agencies assign officers massive caseloads of several hundred offenders and in these scenarios, the individuals under their supervision are not actively monitored.

The terms banked, administrative, and paper probation refer to an inactive status that does not require contact with the overseeing officer. These individuals typically successfully complete their probation if they are not re-arrested during the specified period. To be placed on a banked caseload, an offender is usually identified as low-risk, is convicted of a misdemeanor offense, or lacks an extensive criminal record.

While on probation, an offender is required to comply with all conditions set forth by the supervising authority as well as other elements of the sentence. This includes paying all fines, fees, and restitution applicable in the case. If an offender violates the conditions of probation or commits another offense, then he or he is subject to a probation revocation hearing.

Parole

Parole refers to an offender’s conditional release from a prison to serve the remainder of his/her sentence within the community. Parole is sometimes referred to as re-entry. Not every state has parole, and states employ different statutory requirements. In some instances, an offender might automatically qualify for release after serving part of a sentence. More commonly, an offender can apply to the state parole board for early or discretionary release. If this application is given consideration, a hearing is scheduled. Similar to a sentencing hearing, the parole board may also hear from friends and family of the offender as well as the victim(s) in the case.

The parole board will determine whether the offender poses too significant a risk to be released. If parole is granted, the individual is subject to conditions, and violation of these conditions is likely to result in parole revocation and re-incarceration. DUI offenders who are subject to parole tend to be those who are convicted of serious felony offenses.

Role of community supervision

In most cases, incarcerated impaired drivers eventually re-enter society. Therefore, punishment alone is not a viable long-term solution for addressing the needs of this high-risk population. DUI offenders will eventually have access to a vehicle. To protect the general public, the focus must shift to utilizing a combination of rehabilitative strategies that can produce behavioral change.

Rates of substance use and co-occurring mental health disorders are higher among the impaired driver population. Community supervision officials should rely on validated assessments to determine what issues and needs exist and then partner with other community agencies to connect clients with treatment services.

Community supervision is the nexus of monitoring, accountability, and behavior change.

Figure: Community supervision as a nexus for monitoring, accountability, and behavior change

Common supervision practices

The following tasks are part of the standard workload of most probation officials:

- Conducting pre-sentence investigations and writing pre-sentence reports for the courts

- Meeting with new clients

- Conducting screening and assessment to identify offender risk level and criminogenic needs

- Developing an individualized case plan

- Developing a treatment plan

- Referring clients to services within the community to address foundational needs

- Monitoring compliance and ensuring client accountability

1. Pre-sentence investigations

While the bulk of probation officer workload centers around the supervision of convicted offenders, monitoring can also be required as a condition of pre-trial release. Many jurisdictions have pre-trial service agencies that assume responsibility for the supervision of defendants.

Probation officers also spend significant time assisting the court in advance of sentencing. Once a criminal case enters the sentencing phase, judges require information beyond evidence entered into the record at trial. This pre-sentence investigation requires community corrections/probation departments to compile pre-sentence reports. A thorough PSR should contain the following:

- Summary of offense

- Criminal history including previous sentences/sanctions

- Driver record and any past traffic infractions

- Record of compliance while under community supervision

- Medical (physical health) history

- Mental health history

- Alcohol and drug use (past and present)

- Screening and assessment outcomes

- Treatment history/prior admissions (modalities/approaches previously employed; timeframes between admissions; periods of recovery)

- Personal and family history

- Education

- Employment history and current employment status

- Financial/socio-economic status

If a screening and/or assessment was not conducted at any point during the pre-trial phase, it should be done as part of the pre-sentence investigation.

To further assist in the sentencing process, a list of program options and treatment interventions that are well-suited to the DUI offender’s risk and needs should be compiled and provided to the judge along with the PSR. If a judge is constrained by statute and mandated to order certain conditions (either minimum sentences or participation in certain programs), these can also be outlined in the PSR with recommendations about how various program options either meet statutory requirements. If victim restitution is likely to be part of the sentence, the PSR might also contain a proposed payment schedule.

While the pre-sentence investigation takes place, the convicted DUI offender typically remains under supervision within the community. A judge may impose additional conditions if deemed necessary to protect public safety.

2. Client intake

Following the sentencing hearing, an impaired driver subject to probation is given a date to report to the supervising agency. Generally, this first appointment involves a review of the sentence and associated conditions, a review of the individual’s criminal history including any previous supervision requirements, and a discussion of agency policy and protocols. Probation officers learn more about clients’ education, employment, socioeconomic status, living arrangements, family and dependents, social network, substance use, medical history, potential risk and protective factors.

For individuals who have never had previous contact with the justice system, the prospect of community supervision can be overwhelming. Probation officers can ease concerns by providing a step-by-step summary of what will occur during the term of supervision and how clients can successfully navigate conditions.

3. Screening and assessment

The process of screening and assessment is discussed in detail here.

Assessments are instrumental in assisting probation officers in making decisions regarding the appropriate level of monitoring, caseload assignment, the use of monitoring technologies, the need for substance testing, the need for treatment interventions, and the connection to other ancillary services.

Screening and assessment may have been completed pre-trial or pre-sentence. Probation officers should review these results. However, for the purpose of developing supervision plans and making appropriate treatment referrals, probation departments often rely on other instruments, particularly when it comes to classifying risk level.

The Computerized Assessment and Referral System (CARS), the Impaired Driver Assessment (IDA), and the DUI-RANT (Risk and Needs Triage) can all be used with DUI clients and provide accurate assessment of risk level. Probation departments are encouraged to review current assessment practices and determine whether one or more of these instruments can be utilized. The use of generic assessment instruments, however, will produce inaccurate risk classifications, which could cause probation officers to limit the intensity of supervision for DUI offenders who are actually at high-risk to recidivate.

Screening and assessment should follow the Risk–Needs–Responsivity principles.

Risk. (Whom to target?) Risk should take into consideration both static and dynamic factors. Static risk factors are variables that cannot be changed, such as age, gender, and other factors such as prior criminal history, age of first offense and age of first consumption. Examples of dynamic risk factors include anti-social cognitions, substance use, employment status and more.

Impaired drivers have many protective or pro-social factors that can reduce risk score, so practitioners should be aware that their existing assessment tools may not be appropriate for use among these offenders.

Needs. (What to target?) There are eight criminogenic needs associated with risk: history of anti-social behavior, anti-social cognitions, anti-social personality pattern, anti-social associates, family/marital discord, education/employment, substance abuse, and leisure/recreation.

Examples of non-criminogenic needs include factors such as low self-esteem, mental health disorders, physical health, etc. While addressing non-criminogenic needs may not directly result in reductions in recidivism, it can lead to improved quality of life among clients. Some of these non-criminogenic needs can be directly tied to criminogenic risk factors. For example, the presence of a psychiatric condition increases the likelihood of an individual having a substance use disorder.

Responsivity. (How to target?) Treatment should be delivered in a style consistent with the ability and learning style of the individual. Using tailored interventions is likely to produce better outcomes. Internal responsivity requires therapists to match the content and pace of interventions to individual characteristics, such as personality and cognitive maturity. External responsivity considers such issues as active or passive participatory methods and specialized considerations such as trauma and victimization, gender, culture, etc. Using trauma-informed and gender-sensitive approaches as well as cultural sensitivity when appropriate can improve the experience of programming and treatment. Research examining effective interventions for female impaired drivers found that gender-specific group therapy led to better outcomes as women noted that mixed gender groups created an environment where they did not feel safe sharing their experiences or engaging in the therapeutic process. Likewise, PTSD and trauma often go unaddressed, and merely recognizing the potential of past victimization can be important to facilitate dialogue.

Once probation officers complete the assessment process, the information obtained can be used to inform the development of a case management/supervision plan.

4. Case Management Plans

Each client should have a case management plan that is specific to his or her case. The case plan serves as a roadmap for each client’s term of supervision and should summarize goals, objectives, expectations, and tasks that are to be completed.

The case plan should be developed in collaboration with the client. Clients must believe that success is possible. Case management plans should always be:

- Relevant: the components should be specific to the individual and based on the findings of the assessment.

- Research-based: recommendations and requirements within the plan should be reflective of evidence-based and/or best practices.

- Realistic: the goals and requirements in the plan should all be achievable within the period of community supervision.

Elements commonly found in case plans include the following:

- Client information

- Assessment outcomes including the client risk level and specific criminogenic needs

- Goals to be accomplished during the period of supervision. For each goal, the following must be identified:

- Strategies to accomplish the goal

- Specific actions needed to accomplish the goal

- Role of client and role of probation officer in achieving the goal

- Timeframe for achieving the goal

- List of risk factors and protective factors

- Roles and responsibilities of the client

- Roles and responsibilities of the probation officer

- Conditions that the client must abide by while on probation. This may include reporting schedule, unannounced visits, testing requirements, and education or treatment requirements.

- Conditions of the sentence that the client must complete

- Consequences of non-compliance

- Foundational needs that must be addressed—including housing, transportation, childcare and vocational training. These needs should be identified and prioritized.

- Strategies to address foundational needs including referrals to community partners or organizations

- Treatment needs and referrals to providers

Supervision plans should be reviewed at regular intervals. Clients can provide probation officers with feedback, and if an intervention is not working or a client is not responding to the approach, there should be a discussion about why the current intervention is a poor fit. If a client has demonstrated continued compliance, the review process provides an opportunity to reward this behavior by making adjustments to conditions such as the frequency of appointments or testing or monitoring technologies.

Effective supervision principles. The National Institute of Corrections and the Crime and Justice Institute have developed a framework to guide all supervision programming, including interventions, for high-risk impaired drivers. Agencies that rely on interventions and practices that are consistent with these principles are likely to produce better outcomes.

- Assess actuarial risk/needs – use validated assessment instruments to identify client risk level and criminogenic needs and to guide supervision.

- Enhance intrinsic motivation – to facilitate behavior change, it is important to motivate clients and promote engagement in the treatment process. The development of internal drive has proven to be more effective than external factors in reducing recidivism. Probation officers rely heavily on motivational interviewing to develop intrinsic motivation.

- Target interventions – appropriate interventions should adhere to the Risk–Needs–Responsivity principles. To produce better outcomes, interventions should be tailored to the individual. In addition to identifying client risk, criminogenic needs, and other important programming considerations, practitioners should also determine the appropriate dosage of each intervention.

- Skill train with directed practice – the use of cognitive-behavioral approaches delivered by trained staffed is important for facilitating behavior change. Skills must be practiced by the client to demonstrate that these new techniques can be utilized effectively.

- Increase positive reinforcement – in a criminal justice context, great emphasis is placed on sanctions to correct behavior. But research consistently demonstrates that positive reinforcement can be a more powerful tool and that a ratio of four positive to every one negative reinforcement is optimal to promote change. Probation officers should apply both graduated sanctions and positive reinforcements.

- Engage ongoing support in natural communities – behavior change can be reinforced through the development of pro-social ties and positive support networks. These relationships can be a stabilizing force in a client’s life.

- Measure relevant processes and practices – to ensure that practices are evidence-based, data must be collected, and corresponding outcomes must be measured. Community supervision agencies should conduct evaluations on client progress, staff performance, and overall fidelity to evidence-based models and practice.

- Provide measurement feedback – when data is collected and/or evaluation is conducted, it is important that outcome measures are communicated to both clients and staff. For clients, feedback can help them assess progress and also provide accountability when setbacks or non-compliance occurs. Feedback provides practitioners with information about their performance including the effectiveness of their decision-making.

DUI supervision guidelines. In addition to the general principles for reducing recidivism, APPA has developed six specific guidelines for the community supervision of DUI offenders:

- Investigate, collect, and report relevant and timely information that will aid in determining appropriate interventions and treatment needs for DUI offenders during the release, sentencing, and/or supervision phases.

- Develop individualized case or supervision plans that outline supervision strategies and treatment services that will hold DUI offenders accountable and promote behavioral change.

- Implement a supervision process for DUI offenders that balances supervision strategies aimed at enforcing rules with those designed to assist offenders in changing behavior.

- Where possible, develop partnerships with programs, agencies, and organizations in the community that can enhance and support the supervision and treatment of DUI offenders.

- Train supervision staff to enhance their ability to work effectively with DUI offenders.

- Assess the effectiveness of supervision practices on DUI offenders through both process and outcome measures.

5. Treatment plans

The development of individual treatment plans is the responsibility of clinicians and counselors who have training in the fields of addiction and mental health. Probation officers should utilize needs assessments that are validated specifically among the impaired driver population. Similar to the supervision plan, the treatment plan should outline expectations and include responses to compliant and non-compliant behavior.

Probation officers do not have the training and typically do not utilize instruments that would allow them to arrive at a clinical diagnosis, but they do have the ability to facilitate referrals to clinicians who are better positioned to recommend interventions. Probation departments should be aware of the various treatment providers that operate within their communities. To assist probation officers in the referral process, the Computerized Assessment and Referral System contains a treatment referral database. If the agency has a list of treatment providers, this can be added to the tool and when a client is screened/assessed, a referral list will be generated that matches the client with treatment providers in the community.

Basic treatment plans formulated by probation officers should contain an overview of screening and assessment findings. While the Risk–Needs–Responsivity principles inform probation decision-making, two additional principles are important:

Dosage principle. The amount and intensity of treatment should be matched to the risk level of the client. Dosage encompasses the intensity of treatment, such as residential versus community-based delivery models, and the duration of the treatment. Individuals who have higher risk levels should be exposed to more intensive and longer interventions to facilitate behavior change. Higher-risk probationers require a higher degree of initial structure and more intensive services than lower-risk individuals. On the other hand, overtreating individuals who do not require significant interventions does nothing to improve outcomes. Best practices dictate that during the initial three to nine months of probation, approximately 40-70% of an individual’s spare/leisure time should be occupied; routines should be established and free time should be filled with positive or pro-social activities such as schooling, employment and treatment. High-risk individuals who have unstructured free time have a greater likelihood of engaging in anti-social behaviors including substance use.

Treatment principle. Treatment should be an integral part of the sentence and case/supervision plans for all high-risk clients. Probation officers should identify criminogenic and treatment needs and facilitate referrals to providers in the community who are skilled in these areas. For many individuals, behavior change will not be realized absent significant treatment interventions. In order for programming to be effective, it should be delivered by service providers in a manner that is consistent with the theory and design underlying the intervention.

When developing basic treatment plans for impaired driving clients, probation officers should take the following into consideration:

- Does screening and assessment indicate the presence of a substance use disorder (i.e., alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, both)?

- Does the client believe that their alcohol consumption or drug use is problematic?

- Does the client have a realistic assessment of their level of substance consumption?

- Does screening and assessment indicate the presence of a mental health disorder?

- Does screening and assessment indicate a history of trauma?

- Does screening and assessment indicate the presence of co-occurring disorders?

- Did the client disclose issues with substance use, mental health, and/or trauma? While these issues may not have been formally diagnosed in the past, clients can provide valuable information about the degree to which these issues affect their ability to function.

- Did the client disclose suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempts?

- Does the client’s file indicate previous treatment involvement? If so, what did it entail?

- Did the client disclose previous treatment involvement? If so, what did it entail?

- Have previous treatment interventions been effective in addressing the client’s issues?

- Have certain approaches to treatment been ineffective?

- Has the client participated in self-help or support groups such as AA or NA?

- Does the client have insight into his/her behavioral health issues?

- Is the client motivated to address his/her substance use issues?

- Is the client motivated to address his/her mental health issues?

- Is the client motivated to address his/her trauma?

- If a client has previously been in recovery or achieved a period of abstinence, are there certain risk factors or circumstances that led to relapse?

- Are there other relevant factors to consider when making treatment recommendations, such client gender or cultural experiences?

The more information probation officers are able to collect, the better positioned they will be to make targeted referrals. Probation officers should also explore the level of insight that clients have and whether they are ready to change their behavior. DUI offenders are notorious for having a lack of insight into their behavior as well as their substance use, which can lead to defensiveness and unwillingness to engage in treatment.

One integral part of the treatment plan should be relapse planning as setbacks within treatment should always be anticipated.. Officers should be aware of individual triggers and be cognizant of early warning signs of relapse. Clients who have a strong rapport with their probation officer might disclose relapse or indicate that they are considering consuming alcohol and/or using drugs. As relapse is part of the cycle of addiction, when a client returns to using substances the primary focus should not immediately be on punishment but rather linking that individual with clinicians and helping re-establish recovery.

Impaired drivers as a supervision population: Not the usual suspects

Guidelines for the supervision of DUI offenders exist because this population is unique when compared to other justice-involved groups.

People from all walks of life and circumstances are routinely arrested for DUI. However, there are some common characteristics that have been identified through decades of research. Impaired drivers are generally younger males (most are between the ages of 20 and 45, and the majority are under 30), although in recent years, women have accounted for a greater percentage of individuals arrested for

impaired driving—approximately 25%, according to the most recent FBI Uniform Crime Reports.

Other common characteristics of impaired drivers are that they are frequently Caucasian, have a history of unstable relationships, and tend to be educated and employed at higher rates than other justice-involved individuals. Subsequently, they are often of higher socioeconomic status, which is reflected in their ability to retain specialized defense counsel in many instances.

“First” offenders. Studies typically separate impaired drivers into two categories—first-time offenders and repeat offenders.. It is important to remember that the term “first offender” can be a misnomer as it is highly unlikely that an individual who is caught driving under the influence has only engaged in the behavior one time. Research has found that impaired drivers can operate a vehicle more than 200 times before being detected. It should be no surprise then that both first and repeat offenders may display similar issues. This is why it is important to screen and assess every individual offender regardless of the criminal history. A first-time offender can easily be a repeat offender who has managed to avoid being caught.

While first-time DUI offenders may lack an extensive criminal history, it is not uncommon for these individuals to present with substance use issues. Many first offenders have blood alcohol concentrations that are more than double the limit, which is indicative of binge drinking. Alcohol use patterns that involve high levels of consumption on limited occasions might be more likely to lead to DUI behavior than patterns of frequent but moderate consumption.

In addition to excessive alcohol consumption, first offenders also display personality and psychosocial characteristics that lead them to engage in risky behavior. These include agitation, irritability, aggression, thrill-seeking, impulsiveness, external locus of control (blaming others for actions), social deviance, non-conformity, and anti-authoritarian attitudes. These occur more commonly among young males, the largest demographic of impaired drivers. If left unaddressed, these factors can develop into more significant personality patterns and criminal thinking, which increases recidivism risk.

The good news is that two-thirds of impaired drivers never return to the criminal justice system. These individuals self-correct and modify their behavior without significant intervention. In these cases, the shame, stigma, costs, or inconvenience resulting from the experience in the justice system is enough of a deterrent to prevent these individuals from engaging in the behavior in the future. Or, these cases may represent the rare instance where an individual made a one-time error in judgment and was unlucky enough to be caught. It is important for supervision authorities to be able to identify these low-risk offenders and apply an appropriate level of monitoring and interventions.

While first offenders are likely to have a lower level of needs than repeat offenders, they can present with both substance use and mental health disorders. Research has shown that among first-time DUI offenders the prevalence of alcohol use disorders is high, with more than 80% qualifying for the lifetime presence of the disorder; 33% of women and 44% of men meet the criteria for past-year disorders. Drug use is also common. In a study that examined primarily first offenders, 30-40% qualified for a lifetime drug use disorder and 10-20% qualified for past-year drug use disorders. These figures are also likely to be an underrepresentation of the extent of polysubstance use among impaired drivers. The presence of a substance use disorder has been shown to increase the likelihood of having other psychiatric conditions.

Repeat/high-risk offenders. Approximately 25% of individuals arrested and 30% of individuals convicted of DUI are repeat offenders. This is the one-third of the population that does not self-correct and should be the focus of intensive interventions. If resources are limited, they should be targeted toward this group of offenders.

For the past two decades, this population was classified as “hardcore drunk drivers.” Responsibility.org coined this term to draw attention to the offenders who account for the majority of fatalities and represent the most significant threat to public safety. It is imperative that efforts focus on these individuals. Hardcore drunk drivers commonly drive with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of .15 or above, and do so repeatedly, as evidenced by having more than one DUI arrest. One other type of impaired driver can be added to this definition. In examining the changing nature of the impaired driving landscape, increased testing has begun to reveal high rates of polysubstance-impaired driving. While the true extent of this problem remains unknown, research has consistently demonstrated the polysubstance use dramatically increases impairment and crash risk. As such, the high-risk impaired driver can be a repeat offender, high-BAC offender, or polysubstance offender or combination of these categories. These are the clients that are more likely to require intensive supervision and more treatment.

High-risk DUI offenders, particularly repeat offenders, have a more defined profile than first offenders. Decades of research has shown that these offenders are overwhelmingly (over 90%) males, Caucasian, and older than first offenders, with the majority under the age of 45. These offenders are more likely to be single, separated, or divorced with a history of unstable or unhealthy interpersonal relationships. When compared to first offenders, they attain a lower level of education, lower levels of income, and have higher rates of unemployment. However, when these offenders are compared to other justice-involved groups, they present with fewer risk factors. For example, DWI court participants (repeat offenders) have higher levels of education, higher rates of employment, and higher socioeconomic status than drug court participants (offenders with multiple drug-related offenses on their records). This distinction is important because it demonstrates how even the most severe DUI offenders can have more protective or pro-social factors than other offender typologies.

There is also an inverse relationship between the number of prior offenses and the age of onset of alcohol dependence. The more severe the offending, the more likely that substance use problems developed at an earlier age.

Rates of drug use are also higher among repeat offenders than first offenders, with 40-70% qualifying for a lifetime drug use disorder. While drug use frequently goes undetected in DUI investigations, the failure to identify this behavior can have significant implications for recidivism.

Additional research has confirmed that female DUI offenders appear to have significantly higher psychiatric comorbidity relative to their male counterparts with diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder being common. Extensive histories of trauma are also present among female impaired drivers.

Repeat offenders are also more likely to exhibit cognitive deficits that develop as a result of long-term substance abuse. Repeat offenders who display these deficits have difficulty processing information, exhibit short-term memory loss, and might have difficulty planning ahead and adhering to supervision or programming requirements. These deficits create challenges for engaging in treatment as offenders have limited ability to process and retain information or learn new skills.

Pathway to offending: Addiction or anti-social?

The high rates of substance use disorders among impaired drivers reveal that addiction undoubtedly plays a role in DUI behavior, but it is not always the primary factor. The failure of many repeat offenders to change their thought patterns and actions despite numerous sanctions and past attempts at treatment demonstrates that the anti-social characteristics that are common among habitual offenders may be a more significant predictor of recidivism. The crime of impaired driving involves two elements—consuming substances and making the decision to get behind the wheel despite knowing the risk. Not every individual who consumes or even abuses substances makes the decision to drive. It is this element that requires further examination.

Impaired drivers present specific challenges for the officers tasked with supervising their behavior. There are several reasons why DUI offenders make for a challenging caseload:

- DUI offenders rarely self-identify as criminals. It is common to have DUI offenders claim that they were unfairly targeted or that they were not impaired at the time of the traffic stop. With more protective factors and ties in the community, DUI clients are likely to consider themselves to be “better” than other types of offenders.

- DUI offenders lack insight into the seriousness of their behavior. Alcohol is a legal substance and drinking is a socially acceptable behavior. As such, many DUI offenders do not consider their actions to be illegal. Furthermore, these individuals frequently suggest that the sanctions they are subjected to are an overreach.

- DUI offenders lack insight about their substance use and associated consequences. These individuals may lack understanding about what constitutes normal consumption. Furthermore, studies have shown that even among repeat offenders it is common for these individuals to believe that they do not need to change their drinking patterns to address their DUI behavior.

- Repeat DUI offenders often lack motivation and do not engage. For those offenders who have been through the system multiple times, serving a period of incarceration can be more attractive than being required to participate in an intensive supervision program or treatment.

6. Referrals to community services: Addressing foundational needs

Foundational needs consist of basic necessities that individuals rely upon to function on a day-to-day basis and within the community. While these needs are not directly tied to recidivism and are not always identified when using risk/needs assessments, probation officers frequently determine that these are areas where clients could use support and/or services. High-risk and repeat offenders are more likely to present with significant foundational needs which may be due to their more pervasive criminogenic needs and life circumstances. For example, years of substance abuse and a lengthy criminal record can have a negative impact on a person’s ability to obtain higher levels of education, steady employment, and a livable wage.

Common foundational needs that probation officers can assist DUI clients in addressing include:

- Employment/vocational training

- Education

- Housing

- Transportation

- Life skills

- Financial assistance

- Parenting/childcare

- Healthcare

- Counseling

By creating a community resources map, probation officers can encourage clients to seek assistance that prepares them to address life issues after their period of supervision terminates.

Figure: Example of a community resources map

Throughout the course of the supervision period, probation officers and clients should work together to identify positive influences and peer supports and also identify anti-social or negative relationships that could place clients at risk for relapse or other setbacks. DUI offenders who suffer from addiction need to separate themselves from people, places, and things that have the potential to trigger substance use. This frequently means ending relationships with partners, family members, and friends who engage in substance abuse or are unwilling to abstain from drinking/drug use when in the presence of the person in recovery.

For female DUI offenders, being able to identify toxic relationships and recognizing a lack of boundaries, and how this contributes to addiction, is necessary to change destructive patterns of behavior. Women in recovery should learn to detect the factors that make relationships unhealthy and the ways in which they undermine sobriety and compromise behavior change. Subsequently, female impaired drivers might benefit from additional counseling that focuses on the establishment and maintenance of healthy, stable relationships. This form of counseling can also focus on improving communication skills and promoting a healthy self-image, increased self-esteem, and self-reliance such that these women can extricate themselves from a history of abusive or dysfunctional interpersonal relationships.

Another important consideration for DUI clients who are new to recovery is entering into existing community support networks such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, or other comparable. For individuals who have never entered into a 12-step program, they may not know how to initiate the process; this is one way that probation officers can offer additional support.

6. Referrals to community services: Addressing foundational needs

Once probation officers develop the case management plan and facilitate referrals, the focus shifts to monitoring compliance. High-risk offenders are subject to more intensive supervision, which likely includes unscheduled home and employment visits, frequent random drug and alcohol testing, and the use of a variety of monitoring technologies in addition to required treatment attendance and demonstrated progress in achieving specific goals.

Some probation departments establish dedicated DUI caseloads that involve the intensive supervision of high-risk offenders with a reasonable client to officer ratio. In other jurisdictions, banked caseloads of DUI offenders can number in the hundreds, and under these circumstances, limited monitoring occurs.

Supervision agencies that have more resources at their disposal are better positioned to develop specialized caseloads that are overseen by experienced officers. In jurisdictions with burgeoning caseloads and limited resources, officers may only be able to monitor the status of cases and push paper. This is unfortunately quite common, particularly for misdemeanor probationers, and limits accountability.

Banked caseloads. Terms of probation vary but generally, an individual is either subject to active supervision or banked probation (also commonly referred to as administrative or paper probation). Banked probation is an inactive status where clients have minimal or limited contact with the officer assigned to their case. Banked caseloads are almost always comprised of individuals who are convicted of misdemeanors as well as offenders who are deemed to be low-risk, non-violent, or lack an extensive criminal history. It is safe to assume that probation officers who oversee banked caseloads that contain DUI offenders have probably had minimal opportunities to receive training about the challenges of supervising these clients as well as evidence-based monitoring strategies.

In most states, DUIs are not classified as felony offenses until the third or fourth conviction. This means that many first and second DUI offenders are not subject to active supervision and may be placed on banked caseloads with a limited degree of monitoring. In these instances, high-risk classifications or non-compliance could lead to more intensive supervision, but generally, these offenders will have minimal contact with the probation officer assigned to their case. Unfortunately, placing DUI offenders on a banked caseload can be problematic because there is no way to effectively monitor the progress of each individual. Banked offenders will not receive the level of services that are needed to address criminogenic needs or behavioral health issues. This is unlikely to produce lasting behavior change.

Placement on a banked caseload should be determined based on accurate risk assessment as opposed to the absence of a criminal record. First-time or misdemeanor DUI offenders can have the same level of criminogenic and treatment needs as repeat offenders. Failure to address these needs could lead to future offending.

Active supervision. The type of probation that most people are familiar with is active supervision. Offenders assigned to active caseloads have regular contact with their probation officer and their progress is closely monitored. At the beginning of their supervision period, these individuals work with probation officers to develop an individualized case plan that outlines goals to be achieved during probation, conditions of their sentence, supervision requirements, consequences for non-compliance/violations, treatment referrals, etc. While these offenders receive more attention than clients on banked caseloads, limited resources and staffing can still lead to high caseloads that can become unmanageable. Active supervision caseloads may be segmented by offender type, although it is common for officers to be assigned a mix of offenders.

On active caseloads, the function of probation officers is to ensure that clients are held accountable. This is done by monitoring compliance and tracking progress over the term of community supervision. High-risk individuals who are non-compliant with supervision conditions or high needs clients who require intensive treatment or ancillary services within the community tend to be prioritized.

If clients commit no new violation or offenses, probation terminates according to schedule. Non-compliant offenders are subject to graduated sanctions and may be returned to court for formal violation hearings. Judges have the discretion to revoke probation if they determine that violations are serious enough to warrant incarceration. Individuals who are non-compliant might also have their term of probation extended or be subject to more intensive monitoring.

Intensive supervision. Intensive supervision requires greater resources and is targeted toward high-risk and felony offenders who present the greatest threat to public safety. Placement can be dictated by the nature of the offense, statutory sentencing requirements, extensive criminal history, previous non-compliance while under community supervision orders, or risk assessment outcomes. Furthermore, individuals who are consistently non-compliant with supervision conditions may be transferred from a banked or active caseload to an intensive supervision program.

Clients who are assigned to intensive supervision caseloads or programs have strict reporting requirements. This includes regular and consistent meetings with probation officers, counselors, and other support staff. Due to the potential for violations, these clients also have supervision conditions that frequently include random alcohol/drug testing and active monitoring. It is common for these individuals to be required to use more than one form of electronic monitoring. Probation officers also conduct unannounced visits to clients’ homes and places of employment to assess these environments and identify potential violations.

Repeat offenders have demonstrated through their past actions that behavior change is unlikely absent accountability. Therefore, probation officers must be diligent when monitoring high-risk individuals as they will test boundaries and try to get away with violations. Probation officers must identify non-compliance and take swift, certain, and meaningful action when these offenders fail to abide by the conditions of their sentence and/or supervision. Supervision authorities do have some discretion in applying sanctions, but with high-risk or repeat offenders, violations are more likely to trigger formal hearings. These offenders are at heightened risk of recidivism and judges are less inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt. Therefore, non-compliance among clients on intensive caseloads is likely to lead to probation revocation and these offenders will serve out the remainder of their sentence in a correctional setting.

Specialized DUI supervision units or caseloads are frequently comprised of offenders who require intensive monitoring. The officers who assume responsibility for supervising these high-risk clients should have a greater degree of training and experience. Intensive caseloads have the fewest offenders, but because these are the most challenging and resource-intensive clients, the probation officers who oversee these cases have significant workloads. Impaired drivers on intensive caseloads are not only at heightened risk for re-offense and non-compliance, they also tend to present with a high level of criminogenic and treatment needs.

There are two evidence-based intensive supervision programs that are specific to impaired drivers that are currently implemented in multiple jurisdictions: 24/7 Sobriety Programs and DWI courts. While these programs have significant differences, both target high-risk, repeat impaired drivers. 24/7 tends to be overseen by law enforcement agencies, and DWI courts are led by judges, although probation is represented within the court team.

24/7 Sobriety Programs. The first 24/7 Sobriety Program was established in 2004 in South Dakota. The program has been replicated in multiple states, particularly states with large rural populations. Each jurisdiction customizes the program to meet identifiable goals, and while a few states have implemented the model statewide, 24/7 is most frequently a municipal or county-level program. The 24/7 Sobriety Program is the first statewide program in the country to require offenders arrested or convicted of alcohol-involved offenses to submit to twice-daily breath testing or the mandatory use of continuous alcohol monitoring. Abstinence is a condition of program participation.

The bulk of 24/7 participants are repeat/high-risk impaired drivers although eligibility has been expanded to include other types of offenders whose crimes were tied to substance abuse. Offenders who refuse to participate in the program serve out a period of incarceration. Some states have modified laws to allow 24/7 program participants to obtain restricted driver privileges. Deterrence theory is the primary underpinning of the program as the structure relies on accountability through testing followed by swift, certain, and proportional sanctions for violations.

Sheriffs’ offices or other law enforcement agencies frequently oversee 24/7 programs that rely on the twice daily breath test model. Participants report to the station and if they fail the breath test, they are immediately taken into custody. Probation departments may be involved in this process or in monitoring offenders who are subject to continuous alcohol monitoring requirements. For offenders using these devices, the vendor monitors electronic reports and sends action alerts to participating supervision agencies on a daily basis if violations or tampering are detected.

In addition to breath tests and continuous alcohol monitoring, program participants might also be required to wear drug patches or submit to random urinalyses to ensure that they remain abstinent from both alcohol and drugs. Impaired drivers who participate in 24/7 may be required to install an ignition interlock as condition of program participation and/or license reinstatement; this varies by state. All 24/7 programs operate using an offender-pay model whereby participants assume responsibility for all costs associated with alcohol/drug monitoring. Fees vary depending on the jurisdiction, and some states have established funding mechanisms for offenders who cannot afford program participation.

Several evaluations have found 24/7 Programs to be highly effective in reducing recidivism among repeat impaired drivers. A recent study conducted by the RAND Corporation found that the South Dakota 24/7 Program led to a 12% reduction in repeat DUI arrests and a 9% reduction in domestic violation arrests at the county level. Another study estimated that the probability of a 24/7 program participant being re-arrested or having their probation revoked 12 months after being arrested for DUI was 49% lower than that of non-participants.

Some practitioners are concerned that the lack of treatment integration within the model misses an opportunity to address the behavioral health needs that are pervasive among these offenders. Researchers have begun to explore ways to add an assessment component to the program as this would allow supervision authorities to identify participants who require interventions beyond intensive monitoring and testing. North Dakota, for example, is exploring how the Computerized Assessment and Referral System can be incorporated into the 24/7 program.

DWI courts. Treatment courts are well-established programs across the country that incorporate intensive supervision, accountability, and treatment to facilitate behavior change among high-risk offenders. The first DWI court was established in Las Cruces, New Mexico, in 1995, and since then, more than 700 standalone or hybrid DWI/drug courts have been established. DWI courts are specialized, post-conviction court programs that follow the well-established drug court model and are based on the premise that drunk driving can be prevented if the underlying causes of the DWI offending are identified and addressed. Unlike the drug court model, offenders who participate in DWI courts do not have their convictions expunged upon successful completion of the program.

These courts were developed for DWI offenders who are not deterred by traditional sanctions and are most resistant to behavior change as demonstrated by their multiple convictions. These offenders are classified as high-risk and often have high needs. Entry into a treatment court program is typically reserved for repeat/felony impaired drivers who have not been involved in fatal crashes. In some circumstances, high-risk offenders who do not have multiple convictions may participate.

There has been debate about whether drug-impaired drivers should be placed in DWI or drug courts. The predominant thinking is that because impaired driving is an offense that involves criminal thinking and behavior beyond mere substance use that these offenders belong in a DWI court. The treatment that these individuals are assigned to might closely resemble that of drug court participants, but their monitoring and other requirements should follow that of traditional DWI court participants.

All DWI court participants have individualized supervision and treatment plans that are designed to address their risk level and specific criminogenic and treatment needs. A screening and assessment process is completed with each participant to inform the development of these plans and clients may be subject to further clinical assessment while undergoing treatment for behavioral health issues. Common supervision requirements for DWI court participants include regular court appearances and status hearings, adherence to random drug and alcohol testing and various forms of electronic and/or alcohol monitoring, intensive substance abuse and/or mental health treatment, etc. The minimum length of participation within these courts should be 12 months, and best practices dictate that clients should remain in the program for 18-24 months to facilitate behavior change.

To facilitate accountability and rehabilitation, judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, law enforcement, probation officers, treatment practitioners, and other stakeholders work collaboratively with court participants to meet specified goals. Clients who are compliant with conditions, successful in meeting goals, or demonstrate progress receive positive reinforcement and modest incentives. Best practices dictate that the DWI court judge have regular face-to-face contact with clients and that at least three minutes be spent addressing each participant in court. This simple action has been shown to promote accountability, build rapport, and enhance client motivation.

To achieve reductions in recidivism, DWI courts must maintain fidelity to the National Center for DWI Courts’ Ten Guiding Principles. Research and evaluations have consistently shown that courts that adhere to these principles have better long-term outcomes.

DWI courts that follow best practices are structured in phases. There are frequently five stages including acute stabilization, clinical stabilization, pro-social habilitation, adaptive habilitation, and continuing care. The court team determines when clients should advance from one phase to another. Upon completion of the final phase, clients are then eligible to “graduate” from the DWI court. NCDC recommends that graduation occur only when clients have a minimum of 90 days in the final phase as well as 90 days of proven sobriety.

A study conducted in Michigan by NPC Research found that DWI court participants were re-arrested significantly less often than comparison group offenders who were sentenced to traditional probation; in a two-year period, offenders in the comparison group were more than three times more likely to be re-arrested for any charge and were nineteen times more likely to be re-arrested for a DWI charge than DWI court participants.

The services offered by DWI courts such as alcohol/drug testing, electronic monitoring, and treatment are usually paid for by offenders. The courts themselves, however, have significant start-up costs and require annual funding to cover administration costs. But multiple studies have shown that investment in DWI courts leads to savings over time as these programs reduce recidivism.

Handling Large Caseloads. Probation departments are able to enhance both the efficiency and effectiveness of monitoring, even among offender placed on banked caseloads, through the use of technology. But technology is not a substitute for active monitoring. Unless someone is being alerted to violations and swift, certain, and meaningful sanctions are applied, offenders are unlikely to alter their behavior.

The implementation of automated case management systems, which can be very sophisticated, is one option available to agencies that have large offender caseloads. The benefit of automating more of the monitoring process is that probation officers receive alerts when offenders miss appointments, fail tests, or violate conditions. With banked caseloads in the hundreds, this level of tracking and the ability to respond to violations is not possible without an electronic platform. The most advanced systems have now begun to automate responses to offender actions by supplying probation officers with evidence-based sanctions and incentives that are dictated by analysis of offender profiles and violations.

Monitoring technologies

Officers who supervise DUI offenders should familiarize themselves with the different monitoring technologies that are available. It is also important for officers to know the strengths and limitations of each form of technology and the circumstances in which each device should be utilized. Certain devices are better suited to high-risk or low-risk offenders. Officers should also be familiar with the costs associated with each type of technology as some are far more expensive than others. Unless offenders are declared indigent by the courts of program administrators, they are responsible for bearing the costs associated with the use of these device. Technology always relies on offender pay schemes and while vendors are typically flexible in working with clients of lower socioeconomic status and establishing sliding fee scales, probation departments should be cognizant of the costs that DUI offenders are responsible for during their community supervision.

The following devices and forms of testing are commonly used in the supervision of DUI offenders:

- Ignition interlock devices (IID)

- Transdermal/continuous alcohol monitoring

- Home/remote breath test devices

- Ethylsulfate (EtS) and ethylgucuronide (EtG) testing

- Urinalysis, hair, and sweat patch testing

- Oral fluid testing devices

Older methods for monitoring substance use, such as random breath or blood testing at a fixed location or reporting center, have been largely replaced by newer electronic technologies that facilitate remote testing. Many remote breath testing options are now available that rely on mobile applications and small breathalyzer attachments. Monitoring devices have shown to reduce substance consumption and impaired driving recidivism while they are in use, but once the use of the technology ceases the rates of recidivism increase. This indicates that technology does not change behavior in the long-term. This shows the importance of pairing the use of monitoring technologies with participation in treatment to address substance abuse.

For agencies with large banked caseloads, monitoring technologies can ensure that offenders who otherwise would not be supervised are at least subject to some degree of monitoring. Under these circumstances, the technology should serve as an objective risk assessment tool in that it can identify “low-risk” offenders who are actually higher risk on account of their inability to adhere to abstinence requirements. Continual violations should result in these offenders being moved to an active caseload.

Ignition interlock devices

This form of technology is specific to impaired drivers and is the only technology currently available that separates drinking from driving. Ignition interlock devices (IIDs) require DUI offenders to blow into the device, which is connected to the starter or other on-board computer system, in order to start the vehicle. If the breath sample registers a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) above a defined pre-set limit (typically .02), the vehicle will not start. The device also requires repeated breath tests (commonly referred to as running or rolling retests) while the vehicle is in use to ensure the DUI offender remains sober throughout the duration of a trip.

Interlock technology is sophisticated and is specific to the detection of ethyl alcohol, which means that the devices do not produce false positives when there are other environmental contaminants. The technology is seamless and reliable and is constantly evolving. The interlock records all actions (start attempts, lockouts, rolling retests, vehicle miles traveled, etc.) and this data is stored in the device. Offenders are required to report back to a service center on either a monthly or bi-monthly basis to have the device calibrated and data downloaded. This information is sent to the designated monitoring agency, which usually has the authority to act on any violations or circumvention attempts. Monitoring agencies vary by state and can include licensing authorities (the Department of Motor Vehicles or its equivalent), appointed court monitors, or community supervision agencies. Costs associated with the technology vary and usually consist of an installation fee, monthly servicing fee, and removal fee. Depending on how competitive the interlock market is within a state, some of these fees are waived or greatly reduced. Installation typically costs between $50-100 and monthly servicing fees are around $75. Typically, the cost of IID technology amounts to $3-4 per day, making it one of the more affordable monitoring technologies.

Ignition interlocks are highly effective in reducing recidivism among both repeat (high-risk) and first-time DUI offenders, while the devices are installed. Interlocks have the most potential to reduce recidivism and change behavior when paired with other effective interventions such as assessment and treatment.

More than 10 evaluations of interlock programs have reported reductions in recidivism ranging from 35-90% with an average reduction of 64%. State laws that require interlocks for all DUI offenders were associated with a 7% decrease in the rate of fatal crashes involving a driver above the legal limit (.08) and an 8% decrease in the rate of fatal crashes involving a high-BAC (.15>) driver. This translates into an estimated 1,250 prevented fatal crashes involving a drunk driver (McGinty et al., 2017).

Currently, all 50 states have passed some form of interlock legislation. As of the fall of 2019, a total of 34 states have passed laws with all offender provisions, the majority of which require mandatory installation of ignition interlocks for all DUI offenses, including first offenses. While all states have an interlock program, most have participation rates below 30%. This means that the majority of eligible offenders fail to install the device as required.

Continuous/transdermal alcohol monitoring

A transdermal or continuous alcohol monitoring device typically consists of an ankle bracelet that detects drinking by sensing alcohol that passes through the skin as it is eliminated from the body. The device tests samples of vaporous perspiration (sweat) collected from the air above the skin at regular intervals. Data regarding transdermal alcohol concentration are stored in the device and transmitted to a base station, which then relays the readings to a secure central website where the data can be accessed and reviewed by monitoring authorities. Vendors work with monitoring agencies to set-up these systems to allow for efficient supervision of large volumes of offenders. The monitoring authority is usually the probation or community corrections agency. For those states that utilize CAM devices as part of a 24/7 Sobriety Program, law enforcement agencies frequently serve as the monitoring authority. Upon violation, the monitoring authority notifies the judge. Actions can be taken in a timely manner, ensuring that there is swift accountability. The judge will impose sanctions based on the severity of the offense. The offender pays the costs of the technology, which includes a one-time installation fee and a daily monitoring fee that typically ranges between $10-15, making CAM one of the most expensive alcohol monitoring options.

Unlike an interlock, transdermal technology does not prevent an offender from driving after consuming alcohol. As a result, this technology is commonly utilized to monitor drinking behavior and/or enforce abstinence orders. Transdermal devices are often used in conjunction with or as a supplement to ignition interlocks. This technology is frequently used as part of 24/7 Sobriety Programs and is a preferred monitoring device for high-risk and repeat offenders. Many probation departments require the use of CAM at the beginning of the supervision period and will consider its removal as an incentive for compliant behavior. Conversely, for offenders who are non-compliant, the use of CAM be applied as a sanction.

Remote breath testing/in-home devices

In-home or remote breath testing options are alcohol monitoring devices located in the residence of the user. These devices can be stationary or portable. Home monitoring devices are commonly court-ordered as an alternative to the ignition interlock for offenders who do not drive or own vehicles. Users blow into the device to obtain a measurement of breath alcohol and the results are either uploaded manually by the service provider or delivered over cell/WiFi service to the monitoring authority. The monitoring authority is usually the probation or community corrections agency.

As an anti-circumvention feature, many of these devices also include a camera component that takes a photo when a breath sample is provided. The device costs around the same as an ignition interlock system and functions in a similar fashion. Remote breath testing options are frequently preferred for lower-risk offenders and can be utilized as a step down from more stringent/costly monitoring.

Ethylsulfate (EtS) and Ethylglucuronide (EtG) testing.

Ethyl alcohol is metabolized in the body through several pathways, and EtS and EtG are two common metabolites or biomarkers of alcohol consumption. Both can be detected in the body far longer than alcohol and appear in urine testing for up to a week after alcohol consumption. As a result, this has become a popular testing method. One of the limitations is that exposure to products that contain alcohol (such as mouthwash) can produce positive results. The cost associated with this form of testing varies depending on whether the sample is subject to evidential analyses. Estimates range from $10-75 per test with screening routinely being under $20.

Drug testing (urinalysis, hair, sweat patches)

Probation departments use a variety of methods for monitoring client drug use. Urinalysis (UA) is the most common testing method for drugs, and it can be requested randomly during home visits and scheduled office appointments. Results can be obtained cheaply and quickly. Some drawbacks associated with UA is that it requires that same-sex officers observe sample collection and there is a lengthy detection window; inactive metabolites are detected in urine which reflects past as opposed to recent use.

Hair analysis is another non-intrusive testing method, but it has an even lengthier detection window than UA and often identifies metabolites. Current impairment may not be able to be established using hair testing, although this form of analysis can provide a longitudinal perspective on drug use history. Research has found that hair analysis is less precise for the detection of certain drugs like cannabis. Hair testing for drugs tends to be more cost-prohibitive than urinalysis.

Another form of drug testing that is available to supervision agencies is the use of sweat patches. The sweat patch consists of a gauze pad covered by a protective membrane similar to a bandage. The sweat patch is usually worn on the upper arm for seven to 10 days and then sent to a laboratory for testing. The lab screens for several different drugs and if presence is indicated, confirmatory testing is then performed. Costs for these technologies vary, although the more sophisticated the laboratory testing, the greater the cost of analysis.

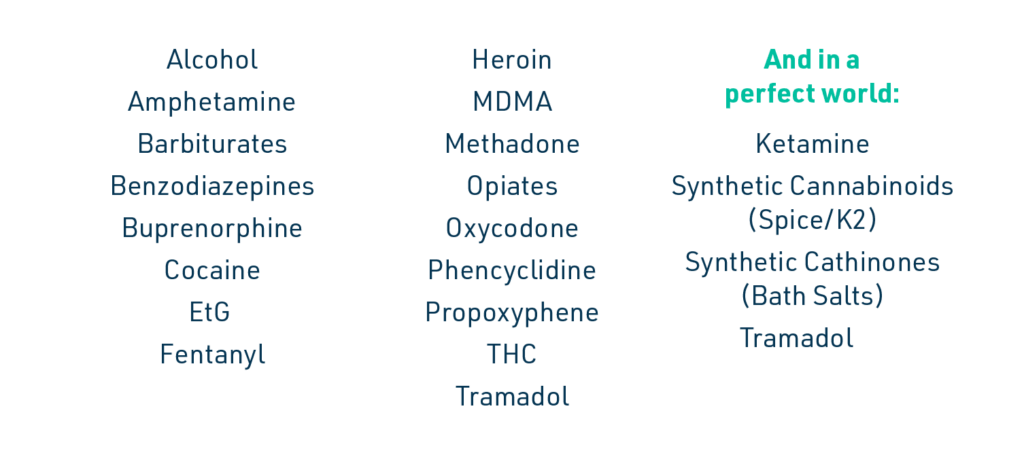

For drug testing among impaired driving offenders, best practices dictate that broad panels be used initially to capture as many substances as possible. This provides the monitoring agency with a good indication of what is being used by clients. The broader the panel, the more expensive the testing, so if offenders screen negative for the majority of compounds then the drug panel should be reduced.

Broad Field Testing TASC recommends testing for

Oral fluid testing

Oral fluid testing devices sample oral fluid (primarily saliva) from glands on the inside of the cheeks and under the tongue with an absorptive device placed in the mouth. The collection device is then sent to a laboratory for analysis, and results are returned to the monitoring agency. These devices are usually used by probation, DUI courts, and treatment facilities to randomly test for drugs. Given that many high-risk impaired drivers are likely polysubstance users who go undetected, the use of this type of technology at the start of the supervision period can help probation officers identify individuals who should be subject to ongoing alcohol and drug testing. For individuals who test negative for drugs after several tests, probation can decide to eliminate drug testing entirely or reduce the frequency of testing and/or the scope of the drug panel.

Oral fluid testing overcomes many of the problems related to urinalysis, which remains the most common method of drug testing within community corrections. Oral fluid testing represents a new tool that is as accurate as urine tests and overcomes the problems associated with sample tampering. Oral fluid is also less invasive. Moreover, the dilution and adulteration tactics that are commonly attempted to alter UA results do not apply to this testing methodology. Another advantage is that the detection window is much shorter and positive results are reflective of recent as opposed to historical use. Oral fluid testing can be conducted onsite in probation departments and results can be analyzed while the officer meets with the client. Costs for this type of testing remain substantial as readers run several thousand dollars and on-site kits can be in excess of $20. These costs will decrease over time as the demand for the technology increases.

Oral fluid testing, in general, is very cost-effective when compared to all other drug testing methods. Because oral fluid collections are easily administered on-site, downtime is minimized because employees are only away from their duties for 10-15 minutes rather than an hour or longer.

Selecting wisely

When determining which technology is most appropriate for DUI clients, probation officers should consider the following:

- Monitoring technologies are situation-based and there are many options available, but testing should be performed because there is no other way to ensure that DUI clients remain sober.

- Match the technology to the client risk level. For high-risk and repeat offenders, begin with more stringent testing methods such as continuous alcohol monitoring.

- Consider testing all DUI offenders for drug use at the start of the supervision period. Use broad drug test panels to capture a range of compounds and synthetic substances. This will help identify polysubstance users.

- Technology can be applied as a graduated sanction. For offenders who are non-compliant with supervision conditions consider the use of continuous alcohol monitoring in addition to an ignition interlock. Offenders who are known to violate should also be subject to as many anti-circumvention features as possible.

- Implement monitoring technologies in accordance with evidence-based practices and guidelines.

- Require timely or real-time reporting of violations. However, if this data is supplied there must be a plan to act upon it. Probation officers should have the authority to apply graduated sanctions that are swift, certain, and proportionate to the violation.

- Recognize client compliance by reducing the frequency of their testing or transitioning to more cost-effective and convenient testing options such as remote breath testing.

- Require offenders who are assessed as having substance use disorders to participate in treatment while subject to the use of monitoring technologies.

- Consider budgetary constraints and the cost associated with different testing methods when determining what options are most feasible for the agency as well as individual clients. In instances where clients lack the ability to pay for the use of technology, identify funding options.

- There is no “one size fits all” approach to the use of technology, and community supervision agencies should have the ability to customize case plans based on client risk and needs.

- Rely on vendors to facilitate efficient and effective monitoring. This includes the use of vendor portals, customized monitoring reports, violation alerts, IT support and troubleshooting, court testimony, etc.

Accountability: Graduated sanctions and positive reinforcement

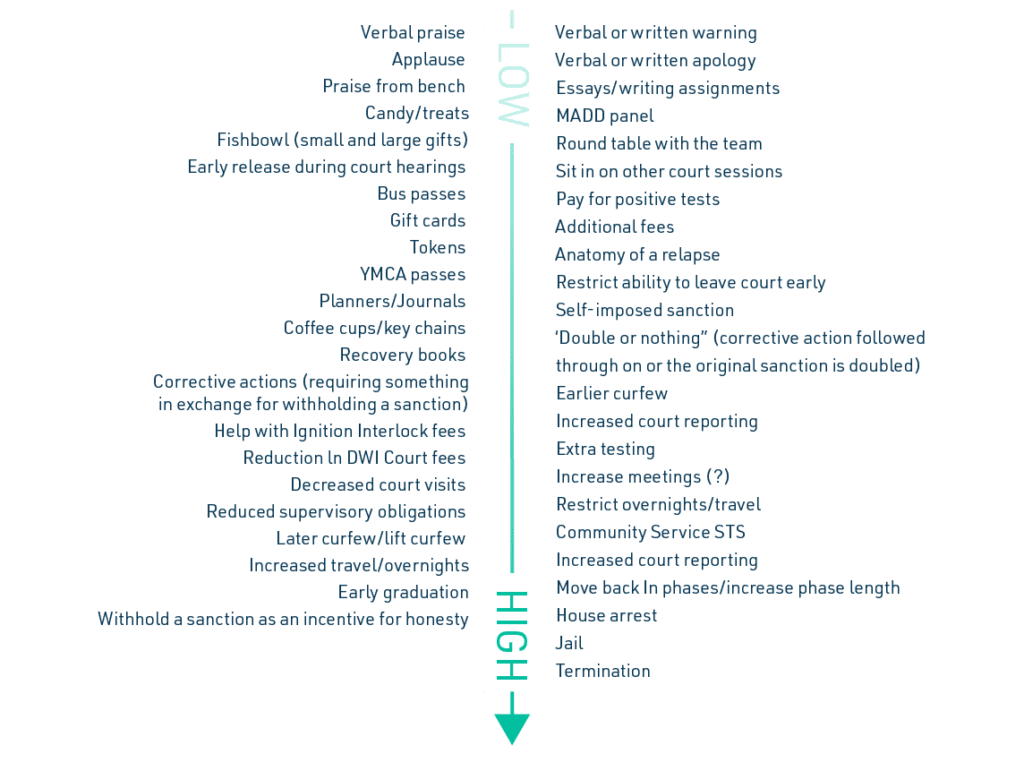

Compliance is achieved when offenders realize that violations do not go undetected and that sanctions are universally applied in response to non-compliance. DUI clients are more likely to test boundaries at the outset of supervision and come into compliance once they realize that their behavior is being actively monitored and that actions will be taken. In addition to graduated sanctions, probation officers can also recognize progress and pro-social behaviors through positive reinforcement. Research has shown the use of reinforcement techniques can be even more powerful than applying punishment when it comes to facilitating behavior change.

Probation officers must strive to achieve the right level of punishment as well as a ratio between the application of sanctions and incentives. For example, sanctions that are too weak can precipitate habituation, in which the individual becomes accustomed, and thus less responsive, to punishment. Sanctions that are too harsh can lead to resentment, avoidance reactions, and ceiling effects, in which the probation officer runs out of sanction options before treatment has had a chance to take effect. Research supports the use of a higher ratio of incentives and positive reinforcement to punishments.

Figure: Range of incentives and sanctions (low to high) in a DWI court setting

Source: South St. Louis DWI Court

Probation agencies using evidence-based supervision practices have adopted policies and guidelines that set forth a range of rewards and sanctions that are appropriate for each type of behavior, the offender’s risk level and criminogenic needs, and the compliance history in the case. Increasingly, the appropriate response for each of the wide variety of compliant and non-compliant behaviors, depending on risk level and the risk factors involved, is set forth in comprehensive but easy to read grids. These should be distributed to clients at the initial intake/appointment and can be reviewed periodically throughout the term of supervision. Sharing this information with clients creates a sense of due process, fairness, and transparency. Some sophisticated case management systems have begun to automate these incentive and sanction grids within the system and can advise probation officers about the most appropriate response in any given scenario.

When determining the most appropriate sanction to apply in response to a probation violation, several factors should be considered:

- Nature and seriousness of the violation

- Client criminal history

- Client violation and compliance history

- Client risk level

- Client motivation level